Letter from Estoril – The Document of Miklós Horthy’s Exile from the Portuguese National Archives

Between 1945 and 1949, nearly 200,000 to 250,000 Hungarian citizens left the country, including those who fled West during the final days of the war or shortly thereafter. In this first postwar migration wave, members of the political and military elite associated with the Horthy era, civil servants, aristocrats, and those compromised during the German occupation sought asylum abroad—among them Horthy himself.

After five years of uncertainty following WWII, former Hungarian Governor Miklós Horthy found refuge in Estoril, Portugal, in 1949. When the Allied powers rejected to receive him due to his controversial wartime role, Portugal — under the leadership of Salazar — offered him dignified exile in the seaside resort of Estoril, just a half-hour train ride from Lisbon.

At that time, Estoril was already known for offering shelter to fallen monarchs, politicians, and members of the émigré elite—earning the nickname “the capital of exiled kings.”

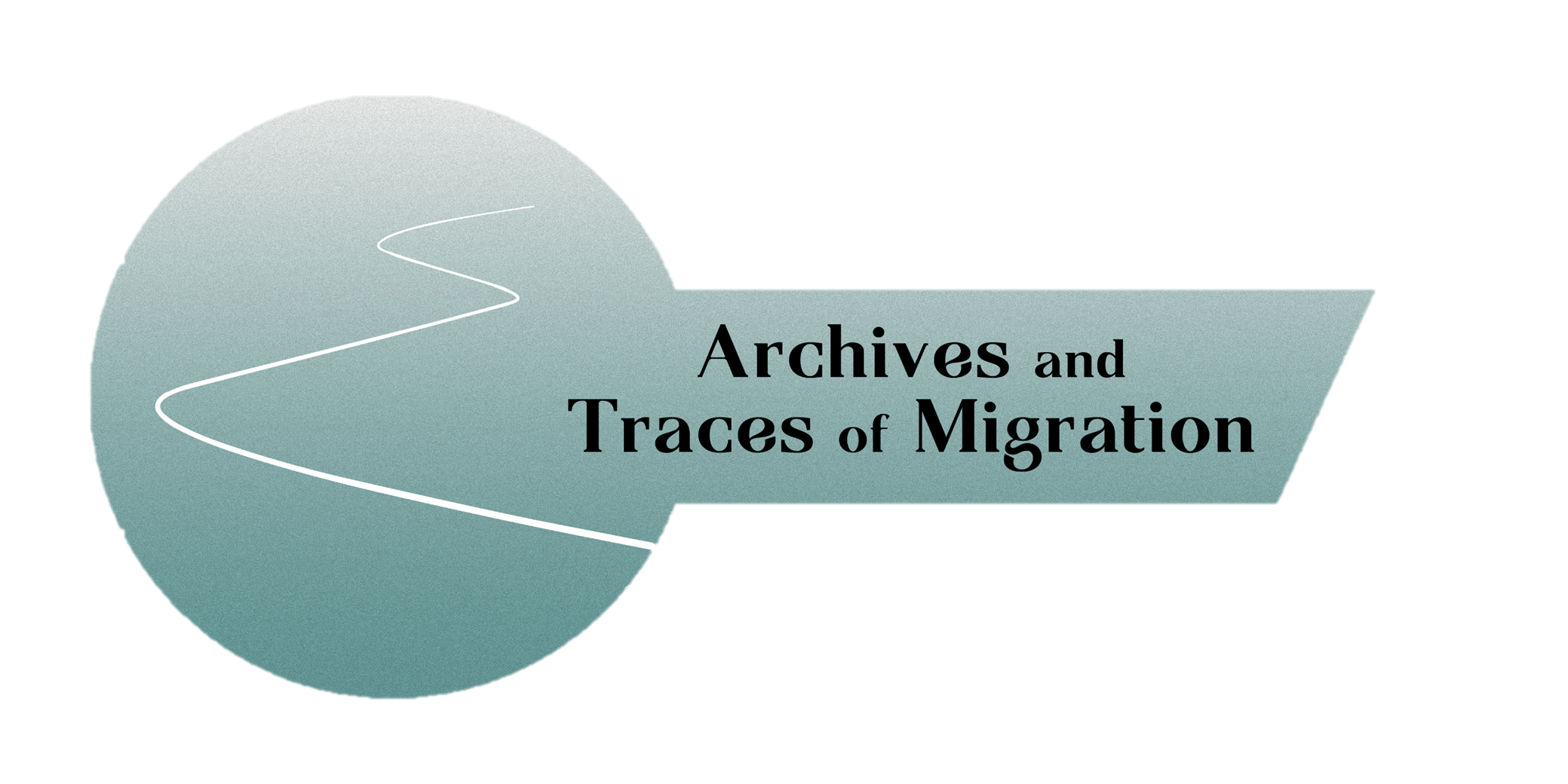

That same year, as Portugal became a founding member of NATO thanks to its wartime neutrality and Salazar’s balanced diplomacy, Horthy sent a personal letter of gratitude to the Portuguese head of state. The handwritten document—shown to me by Portuguese colleagues during a recent visit to Lisbon—is a response to an article in The Times summarizing Salazar’s views on the Atlantic Pact. Horthy not only expressed his gratitude for being received but also took the opportunity to share his current political views.

He agreed with Salazar that the West had made a fatal mistake by allowing the Soviet dictator to expand his influence, sacrificing the sovereignty of Central and Eastern European nations.

“All the keys to the West had been left in the hands of the potentially aggressive Slavs,” Horthy wrote from his own perspective, disregarding that many Slavic nations themselves fell victim to Stalin’s aggression.

The letter is now part of the Torre do Tombo collection—Salazar’s personal correspondence—at the Portuguese National Archives, currently being digitised with support from the European Union’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). Thanks to a growing partnership between the Portuguese and Hungarian national archives, these documents will soon be accessible online, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of Horthy’s final chapter.

Naturally, curiosity led me to visit the villa in Estoril where Horthy spent his final years until his death in 1957, deeply affected by the tragic outcome of the Hungarian Revolution. I found a well-situated but modest building—far from luxurious—perched on a hilltop. Over the years, it had served as a kindergarten and later a guesthouse, and the passage of time had clearly left its marks on the structure.

Levél Estorilból – Horthy Miklós száműzetésének dokumentuma a Portugál Nemzeti Levéltárból

A második világháborút követően, 1945 és 1949 között közel 200–250 ezer magyar állampolgár hagyta el az országot, ideértve azokat is, akik már a háború végnapjaiban vagy közvetlenül utána menekültek Nyugatra. Az első, közvetlenül a háború befejezése utáni időszakban elsősorban a Horthy-korszakhoz kötődő politikai és katonai elit, köztisztviselők, arisztokraták, valamint a német megszállás során kompromittálódott személyek menekültek külföldre, köztük maga a kormányzó, Horthy Miklós.

Miután vitatott háborús szerepvállalása miatt a szövetséges hatalmak elutasították, hogy befogadják, négy évvel a háború után Portugáliában telepedhetett le, ahol António de Oliveira Salazar nyújtott számára méltóságteljes száműzetést a fővároshoz közeli, tengerparti Estorilban. A Lisszabontól alig félórás vonatútra fekvő városka ekkor már ismert volt arról, hogy több bukott uralkodónak, politikusnak vagy emigráns elitnek biztosított menedéket, úgy is emlegették, mint a száműzött királyok fővárosát.

Ugyancsak 1949-ben történt, hogy háború alatti semlegességének és Salazar kiegyensúlyozott diplomáciájának köszönhetően Portugáliát alapító tagként hívták meg a NATO-ba. Ez volt az apropója annak a személyes hangvételű levélnek, amelyben Horthy nemcsak megköszönte a portugál államfőnek, hogy befogadta, hanem egyúttal aktuális politikai nézeteit is kifejtette. Horthy teljes mértékben osztotta a portugál elnök véleményét: úgy vélte, a nyugati hatalmak végzetes hibát követtek el amikor hagyták a Szovjetuniónak, hogy kiterjessze a befolyását Közép- és Kelet-Európa országaira.

„A Nyugat kulcsai mind a potenciálisan agresszív szlávok kezébe kerültek.” – írta, sajátos nézőpontjából figyelmen kívül hagyva azt a tényt, hogy számos szláv nemzet maga is áldozatul esett Sztálinnak.

A levél ma a Portugál Nemzeti Levéltár, a Torre do Tombo fondjában, Salazar levelezésének gyűjteményében található, portugál kollégáink most éppen az Európai Unió Helyreállítási és Ellenállóképességi Eszközének (RRF) támogatásával digitalizálnak. A portugál és a magyar nemzeti levéltár közötti egyre szorosabb együttműködésnek köszönhetően a közeljövőben ezek az iratok is hozzáférhetők lesznek az interneten, hozzájárulva a kormányzó élete utolsó szakaszának teljesebb megismeréséhez.

A levéltár után a kíváncsiság engem is Estorilba vezetett, hogy megkeressem a villát, ahol Horthy 1957-ben bekövetkezett haláláig élt. A dombtetőn elhelyezkedő, távolról sem fényűző ház az évek során óvoda és vendégház is volt, és ez, no meg az eltelt évtizedek jól láthatóan nyomot hagytak az épületen.

Miklós Horthy (1868–1957) in exile in Estoril, Portugal.

Source: https://mandadb.hu/tetel/78499/Horthy_Miklos_Estorilban

Collection of Kállay, registration number: 2008.240.1.

The Population Exchange Files:

Preserving Stories of Resettlement and Compensation

And then there were changing borders and people who lost their citizenship overnight: the ground that slipped away from under their feet.

History often tears communities apart and forces individuals into decisions that define their lives. In his oral history interview, conducted as part of the AToM project, József Attila Prize-winning writer and poet László Tóth shares his personal journey and what it feels like to live as a ‘border person. ” No matter where we start—whether from the past moving forward, or from the present looking back—we always end up at Trianon. It’s this fracture line, a fault in Hungarian history. And not just in history, but in the lives of Hungarians, in the lives of Hungarian people, too.”

His family history perfectly illustrates the traumatic events of living between changing borders in post-war Hungary in the 20th century. His ancestors lived in Izsa, a small village, which in the 20th century repeatedly changed countries and identities. His grandfather, born in 1901, was born in the Kingdom of Hungary, but by 1918, with Trianon looming, the family became “Czechoslovakian,” not by choice, but by the arbitrary shifting of borders. The family didn’t move, yet their citizenship and identity shifted along with the changing political landscape.

Perhaps the most dramatic part of the story is the post-World War II period when Tóth’s family faced forced relocation. As Tóth remembers, families were selected for deportation as “modern-day slaves” to Czech landowners. “It was like a slave auction,” he recalls. ” Young men and women were chosen based on who could work harder, who were healthier. When my mother’s family was still under threat of deportation to Czechoslovakia, she decided that she would marry Géza Varga (my father), and they went to Budapest. So, I was born in Budapest to two genuine Izsa natives, and that’s how I became, in a way, a “wandering person”—someone neither here nor there, a person between borders. He continues: “Somehow, my grandparents managed to get a letter from the Hungarian consulate in Bratislava, which placed them on the list of those to be relocated to Hungary, granting them protection from being deported to Czechoslovakia. This was how one part of the family escaped deportation, but there was the other issue: relocation to Hungary. My father’s parents didn’t escape and were deported to Kocsola.”

Their citizenship changed: his maternal grandparents who remained in Izsa received Czechoslovak citizenship. His parents and he were already Hungarian citizens.

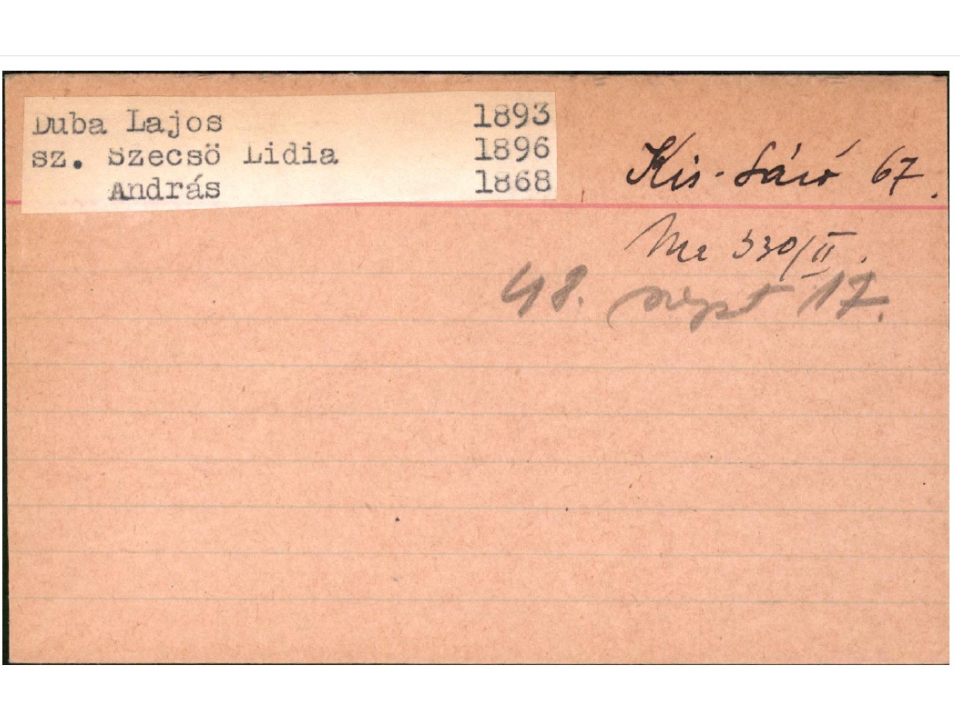

The mid-20th century reshaped Central Europe, leaving deep scars and narratives of resilience. Among these are the stories captured in the Population Exchange Files, now held at the National Archives of Hungary. These documents chronicle a tumultuous chapter in history, highlighting the resettlements and compensations that followed World War II.

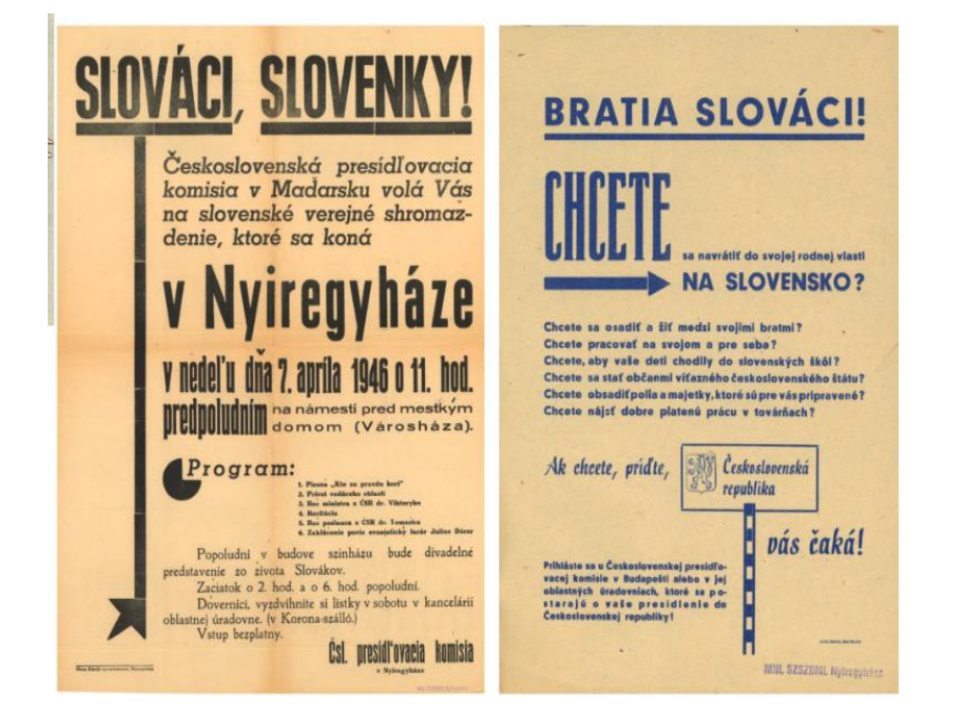

The 1946 agreement between Hungary and Czechoslovakia was a cornerstone of these events. Approximately 72,000 Slovaks voluntarily moved to Czechoslovakia from Hungary, while 45,000–120,000 Hungarians were forcibly relocated to Hungary.

Illustration 4.

The relocation was not just about shifting borders but also about reshaping national identities. Political tensions and economic needs, such as labour shortages left by the deportation of the German population, fuelled the process, especially in mining regions.

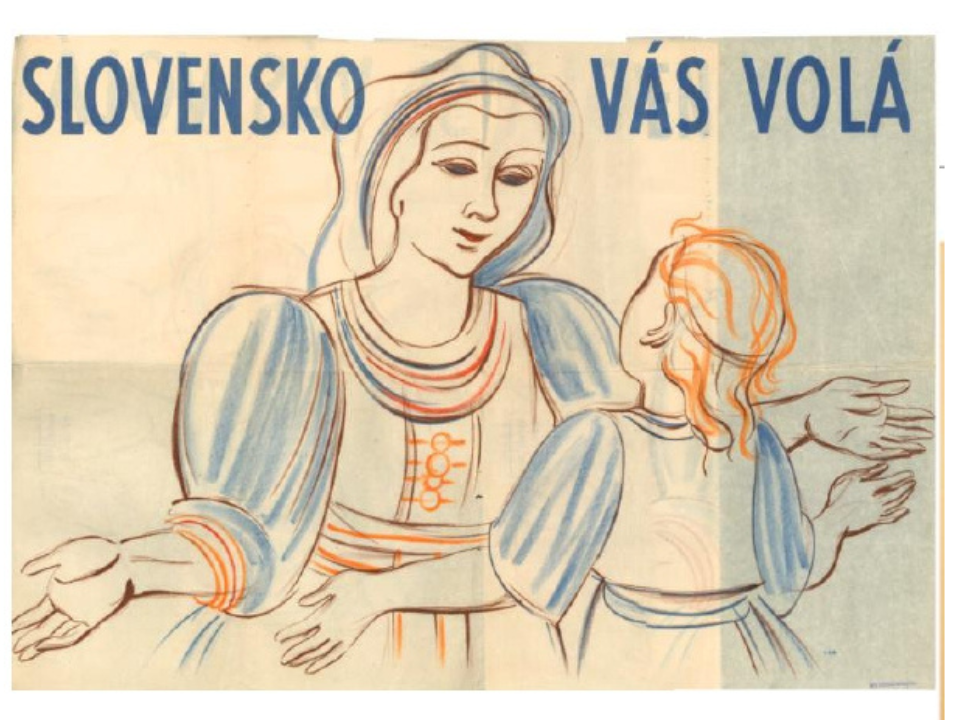

These movements were often accompanied by propaganda, such as the 1946 poster published by the Czechoslovak Resettlement Committee with the motto “Slovakia is waiting for you!”

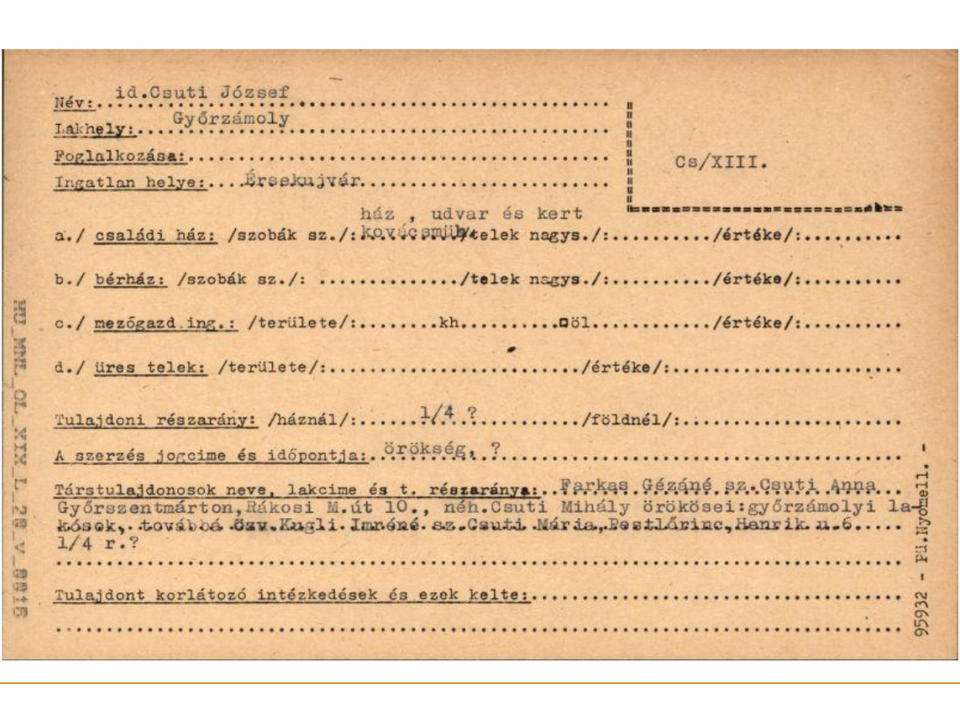

The files encompass transportation records and compensation documents, providing invaluable insights into the lived experiences of individuals and families. They reveal the hardships faced during relocation—people could carry only limited belongings, leaving behind homes and lands. The principle was to compensate the displaced, therefore records were kept not only of individuals, but also of abandoned properties.

Declaration of properties remaining in Czechoslovakia helped the compensation processes, which took place decades beyond the relocations. Between 1964 and 1969, Hungary offered reparations for lost properties, such as houses and lands. Detailed records of these cases remain a testament to the resilience of those affected.

Today, these archives serve as critical tools for understanding history. They connect us to the human experiences behind population policies and illustrate the enduring importance of preserving such documents.

The volunteers of National Archives of Hungary are currently working on indexing population exchange files as part of the Community Archives program, within the framework of AToM project, recording and organizing key data from the documents. Our volunteers work on a dedicated, user-friendly platform developed specifically for these types of projects and receive support through a Facebook group.

Prepared as part of the AToM project, based on the research and writings of Ildikó Szerényi, as well as the oral history interview with László Tóth conducted by Tibor Mészáros and Zsolt Bánki.

How the work of many volunteers helps identify immigration in Limburg, the Netherlands

The Regional Archives of Sittard-Geleen (previously Archief De Domijnen) in the Netherlands is supported by volunteers. They help us to make our archives and collections more accessible than we ever could without them.

There are about seventy volunteers currently working at the archive in Sittard. Some work for the archive, some for the AEZEL project (more about this later), and some work for both. Some of them start volunteering because they retired and want to contribute, or enjoy the social aspect; others are in a reintegration project after a period of sickness to get back in the ‘workflow’; and there are many other reasons why someone decides to join us. Whatever the reason is, many people help us and they are proud of their work. As they should be, because this has turned AEZEL into an amazing resource for finding information; and they help the archive in making our sources more accessible as well.

They do many different activities: they do what they can do best and what they like to do. For example, there are people scanning registers, while there are others who are indexing the contents, transcribing old texts or describing photos.

And it is especially the work that they do for AEZEL that is interesting for identifying migration.

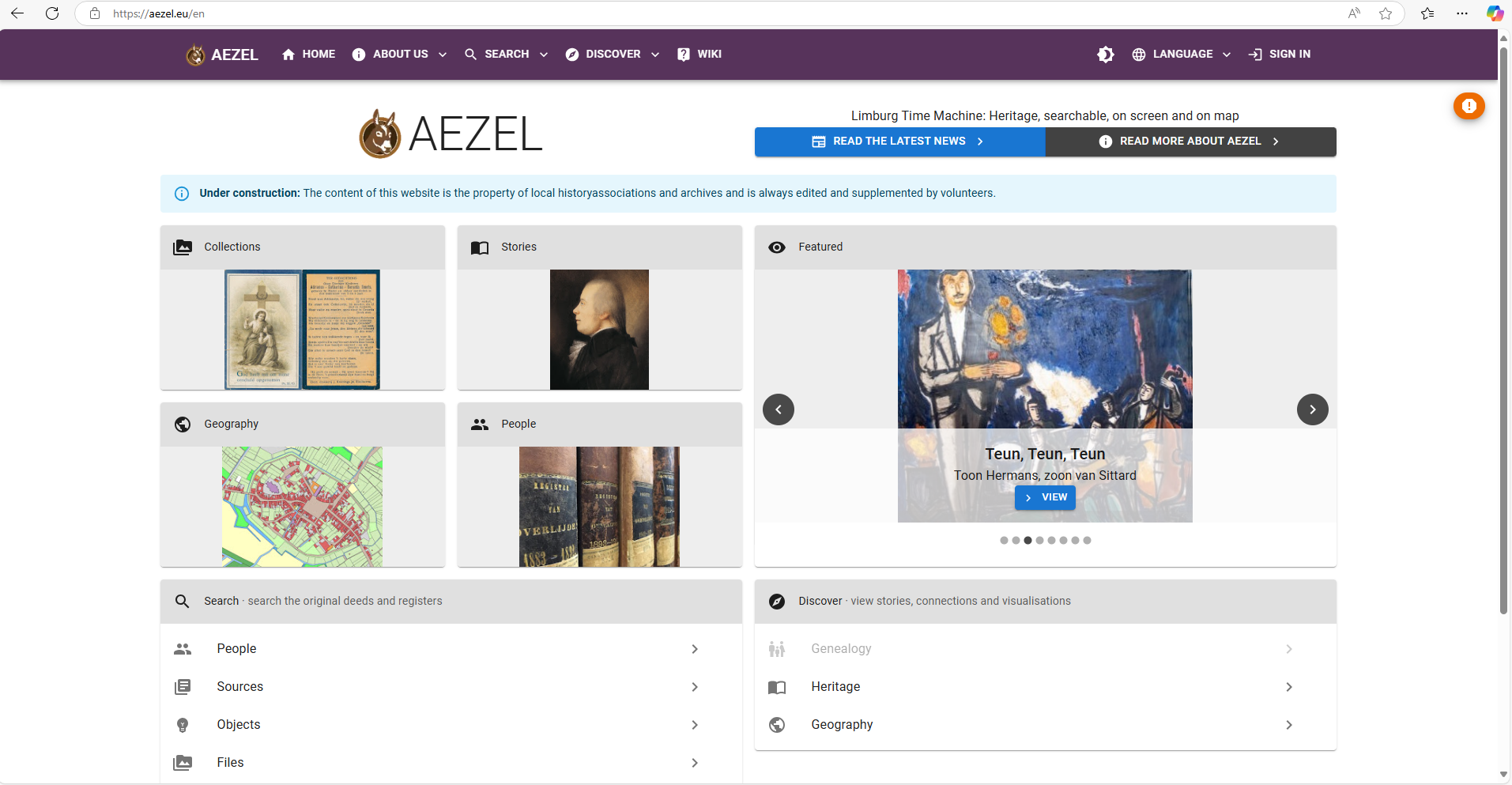

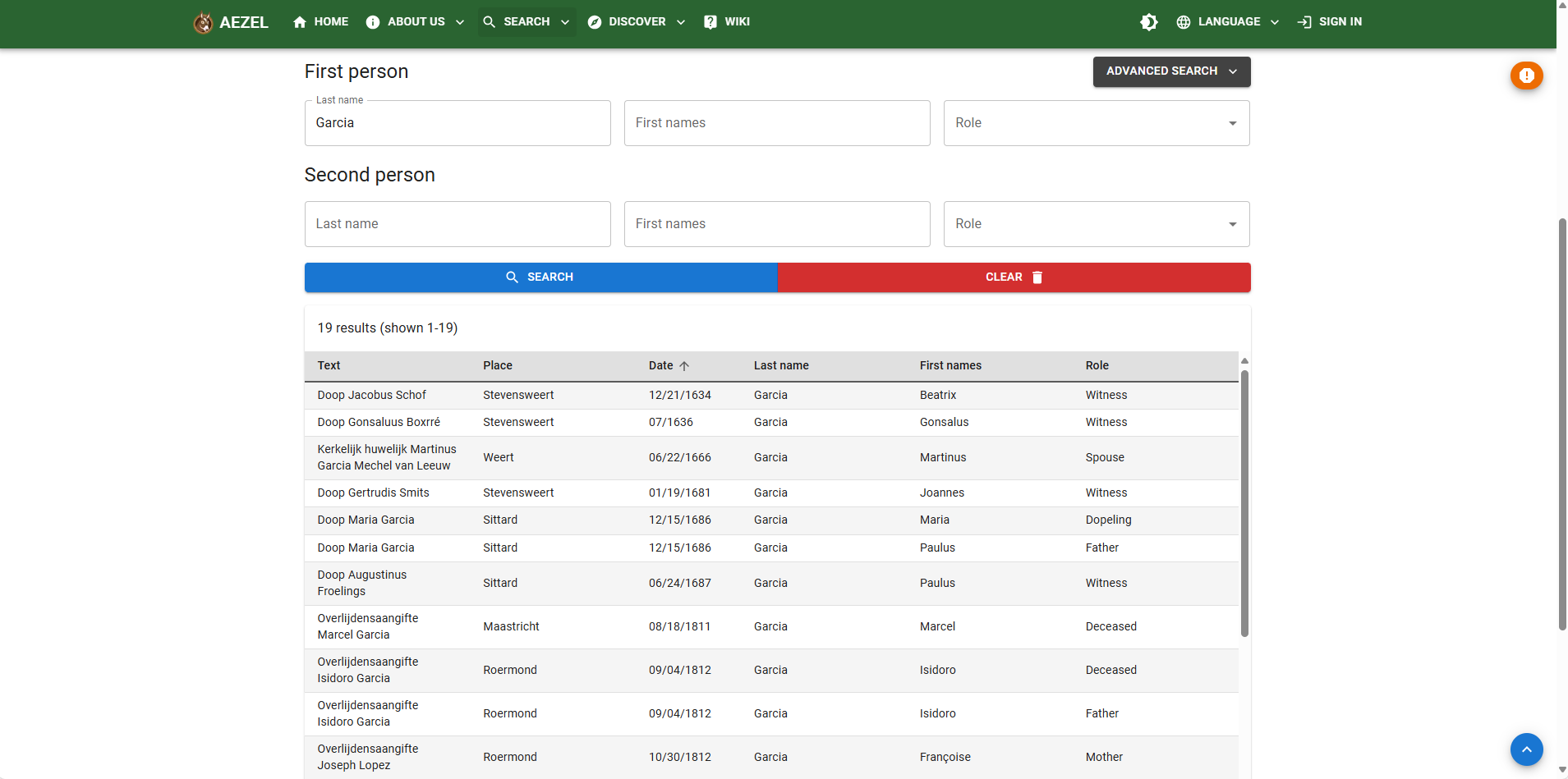

AEZEL (https://aezel.eu/) is a website dedicated to the history of the people of the province of Limburg. Its power lies in the indexed registers and the fact that it always refers back to the original document and when possible, adds scans as well. There are several objects of research in AEZEL: you can search for people, you can search the cadastre, and there are all kinds of stories and collections.

Searching for people is the most interesting when researching migration, though the cadastre can also provide some helpful information.

But there are many more, and smaller, traces of migration. For this, we asked for the help of our AToM-partners in Spain, Hungary and Croatia, who provided us with some typical family names from their countries.

We found plenty of results, too many to go into much detail. We will present the results of the names and a few interesting examples.

A few things to note:

– While searching AEZEL, accents on vocals were left out because they gained no search results (Garcia instead of García).

– The places of birth of the individuals were not studied (and definitely not always recorded!). Therefore, names that are common in several countries could have gained some ‘false’ search results.

– This overview does not show their reasons for migration. There are time periods in which you can guess why people came to our region. For example, there was a Spanish garrison in Stevensweert, from which a register of baptisms and marriages is preserved. There was also a lot of migration to the province of Limburg in the first half of the twentieth century due to the work in the coal mines. But we don’t know if that is the case for all the individuals listed.

– In some cases, we found many search results. For example for Martínez, we found 46.227 search results which also included Meertens, Martijn and Martens. Therefore, in these cases, we searched “Martinez” to exclude alternative spellings.

AEZEL (https://aezel.eu/) is a website dedicated to the history of the people of the province of Limburg. Its power lies in the indexed registers and the fact that it always refers back to the original document and when possible, adds scans as well. There are several objects of research in AEZEL: you can search for people, you can search the cadastre, and there are all kinds of stories and collections.

Searching for people is the most interesting when researching migration, though the cadastre can also provide some helpful information.

But there are many more, and smaller, traces of migration. For this, we asked for the help of our AToM-partners in Spain, Hungary and Croatia, who provided us with some typical family names from their countries.

We found plenty of results, too many to go into much detail. We will present the results of the names and a few interesting examples.

A few things to note:

– While searching AEZEL, accents on vocals were left out because they gained no search results (Garcia instead of García).

– The places of birth of the individuals were not studied (and definitely not always recorded!). Therefore, names that are common in several countries could have gained some ‘false’ search results.

– This overview does not show their reasons for migration. There are time periods in which you can guess why people came to our region. For example, there was a Spanish garrison in Stevensweert, from which a register of baptisms and marriages is preserved. There was also a lot of migration to the province of Limburg in the first half of the twentieth century due to the work in the coal mines. But we don’t know if that is the case for all the individuals listed.

– In some cases, we found many search results. For example for Martínez, we found 46.227 search results which also included Meertens, Martijn and Martens. Therefore, in these cases, we searched “Martinez” to exclude alternative spellings.

Spain

Name | Search results

García 19

Rodriguez 17

González 3

Sánchez 8

Fernández 11

Pérez 70

Martínez 19

López 7

Hungary

Name | Search results

Kovács 4

Nagy 2

Farkas 5

Papp 1

Horváth 5

Croatia

Name | Search results

Horvat 4

Horvatić 0

Knežević 0

Lovrić 0

Kovač 15

Kovačević 0

Lončar 0

Novak 14

Kralj 0

So, we find many more search results for Spanish names. These also go back much longer than the Hungarian and Croatian names. That isn’t surprising given our history. The register from the Spanish garrison goes back to 1633, while Hungarian and Croatian names are mostly found in the 20th century – most likely because of the work in the coal mines.

One name we’re delving into a bit more, is Horvat and Horváth because of the similarity of the names. For a few of the search records, a place of birth is recorded, and it shows that the people with the name Horváth are indeed from or related to someone from Hungaria:

Horvat:

Marriage of Josef Zorko and Maria Potisek in 1914; both born in Austria. Josef Zorko’s mother is called Anna Horvat; no place of birth recorded.[1]

Marriage of Georg Kocijan and Elena Kassak in 1922. Georg Kocijan’s mother is called Helene Horvat; Georg is born in Svibovec; Croatia.[2]

Horváth:

Death of Theresia Horvath in 1931. She was born in Erdöhat, Hungary.[3]

Prayer card of Márton Krajnc from 1982. He was married to Christina Horvath. Márton was born in Sopron, Hungary.[4]

Prayer card of Elisabeth Horvath from 1996. She was born in Bezenye, Hungary.[5]

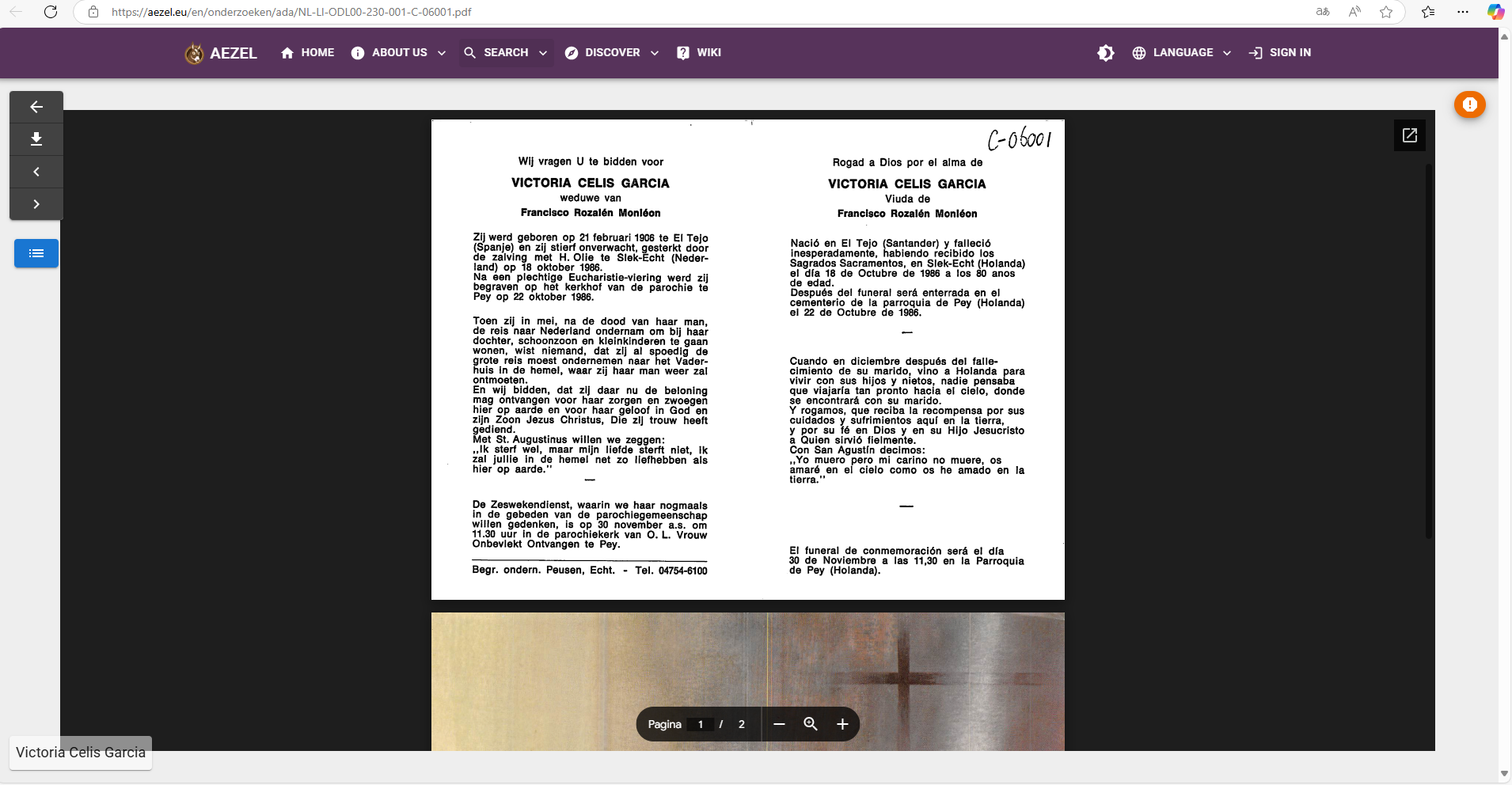

Another interesting example is the bilingual prayer card of Victoria Celis Garcia. She was born in 1906 in El Tejo (Spain) and passed away in 1986 in Slek-Echt (the Netherlands). In her prayer card, a short description of her life is given and apparently, her daughter had already moved to the Netherlands, and after Victoria’s husband passed away in Spain, she moved to the Netherlands to live with her daughter, her son-in-law and her grandchildren.[6]

[1] https://aezel.eu/nl/details/feit/368054

[2] https://aezel.eu/nl/details/feit/315063

[3] https://aezel.eu/nl/details/feit/778023

[4] https://aezel.eu/nl/details/feit/980164685

[5] https://aezel.eu/nl/details/feit/980126776

[6] https://aezel.eu/nl/details/feit/980051124

By searching for these names, we have found several traces of migration. It doesn’t show us why someone migrated, and not always is recorded where someone was born, but it gives us a first impression of some people who have migrated to the Netherlands. An especially interesting resource are the prayer cards, because some of them tell a personal story.

It is the countless hours of work done by volunteers who make this research on individual migrants possible, who make it possible to trace our family histories across Europe and even beyond. And more data will continue to be added in the years to come. The fact that the website is in English, French and German as well, allows many more people to study them from abroad.

Thank you!

Nina Vogels

Migration Records and Community

Inspired by the needs and objectives stated by the AToM Project, author Ellen Engseth explores her work as curator at the Immigration History Research Center Archives through this AToM framework.

The Immigration History Research Center Archives (IHRCA) at the University of Minnesota Libraries makes available and preserves unique and rare sources on im/migrant experiences to North America. We were founded in 1963 as the “Immigrant Archives,” a unit within the university library. Recognizing immigrant settlers as important to the historical and contemporary understandings of the USA and Canada, and that these experiences were often missing from then-established archives, the founders’ vision — which remains true today — was to fill these gaps in institutional archives. For decades following, the material collected to remedy this lacuna comprised the heart of an academic research center that was itself helping to develop the subfield of immigration history. This research center was intended certainly for scientists and academics such as historians and students at the university, yet it also succeeded in centering others who used and/or created these archival collections — those people represented in the historical records.

Many of those record creators were recent arrivals to North America; others were second- or third-generations with identity, ethnicity, and commemoration interests; an additional area of collecting was with organizations who worked with migrating people (e.g. social services agencies, or academic centers that studied immigrants and refugees). Then and now, these community-based contributors are central to our archival mission. With these essential community partners, we’ve co-created a rich repository of personal papers as well as organizational records. Our work at the IHRCA continues to include community, as we seek to remedy more lacuna in the historical record by including those who are not yet represented. Further, we support others in their archival work. And we support research inquiry whether from within the University of Minnesota or elsewhere; in fact, the majority of our project partners as well as our researchers are from outside our university. Many are international, a recognition of the present global interest in migration as well as the diasporic connections to our collections.

At the IHRCA, we have the opportunity as well as responsibility to do more than acquire and share holdings. We seek to engage communities represented in the archives, and those not yet represented, to connect past with present, and to evolve in our own archival work. As is AToM, I am interested to “…position…archives as places of communication among communities, cultures, and time periods.” 1 Though archives are always active, living spaces and places, it takes intention and care to meet the broader archival “social responsibility” mission noted by Tamara Štefanac,2 and to develop community. A social, community-engaged archives is animated by a variety of people, communicating, creating knowledge, and participating in archival actions.

Archives can be a social space and a site for communication among cultures and for building community. How does an institutional archives craft themselves as such a place? One way is to invite the public and their inquiry in. We’ve enjoyed hosting community-oriented events, and we encourage the use of our building by the public. We’ve sponsored artists critically engaging with the collections, for example. And mutually beneficial short-term work residencies, with visiting local as well as global archivists, have been particularly rewarding and instructive to me. These provide a valuable path to AToM objective 2, connecting archivists such as myself who are not members of migrant communities with members of respective migrant communities.

As AToM recognizes, additional training and resources for institutional archivists are necessary to this work.3 It is through learning from others and evolving professional understandings that our archival missions will meet social responsibility, and our methods will change. I believe that this calls for expanding theory and practice. Then, new and altered method can help to right the power imbalances and social insensitivities embedded in institutional archives. For example, how do we accomplish appraising, describing, and representing holdings in more sensitive, inclusive, and diverse manners?4 There are many diasporic, indigenous, and migrant archivists leading this theory and practice. In addition, all of us regardless of identity and experiences can learn more about cultural competency, anti-racist action, and inclusive archival practices. Some of this work need not be complex: Dr. Ricky Punzalan, speaking at the University of Minnesota about the removal of harmful language found in archival description, stated the simplicity of what archivists must do: “not offend people.” 5

How might we meet the AToM objective 3, the co-creation of cultural products with migration community members? Methods may include:

-Ask record creators to write their own historical notes and publish these in the finding aid.

-Provide full and equal attribution of community contributors, if anonymity is not requested.

-Rather than accepting material into the holdings of an established archives, can support be provided so that it remains in community, in a community archive?

-If community members are not on staff already, pay community consultants to process the holdings or to determine access levels to the materials.

-If accepting material donated by community members, honor the donor as the primary party in the relationship.

-Retain the global languages used within the community or the material, thus supporting language justice.

-Ask donors of materials how they prefer to be identified, and use only those terms in description and promotional materials.

AtoM asserts the importance of community members participating in the archival mission, co-creating their migration histories and representations of past.6 As discussed above, our experiences at the IHRCA include working with records creators and keepers in a shared recognition of the value of the materials. Only when it is appropriate for them to share it with the archives (and by natural extension other people), we then steward this material into the future. I feel that the relationship begins here, not ends. At the IHRCA, we hope that community will soon think of the archives, and conduct research in their (and others’) material. We have hosted donation events, marking the exchange of materials from one party to another; ideally these are followed by more visits from those who now feel comfortable with the archives, and are excited to be in the place where their earlier donation is cared for and are accessible to the public. Co-curation of physical or digital exhibits are another natural area for different expertises to create an archival product together.

Archival participation can be a powerful act, as archival actions involve self and group agency. While migrating peoples and their records are often multinational and dispersed, some are local and proximate. And such records can help to fill the loud silences that exist in institutional archives, and can represent more people. Our archival work will change as we seek and meet our social responsibility to care for the experiences of all community members. The objectives of AToM can lead us to social, inclusive, and community-engaged archives of migration.

Footnotes:

1 Project AToM “Brochure,” page 1, https://projectatom.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Project-AToM-Brochure-EN.pdf

2 Project AToM blog post, “Impressions about Migrations from an Archival Perspective,” https://projectatom.eu/index.php/blog-2/ 3 Project AToM “Background Rationale and Objectives,” https://projectatom.eu/index.php/project/background-rationale-and-objectives/

4 Project AToM “Background Rationale and Objectives,” https://projectatom.eu/index.php/project/background-rationale-and-objectives/

5 Dr. Ricky Punzalan, “A Step Towards a Decolonial Future” lecture, University of Minnesota, February 23, 2024

6 Project AToM “Background Rationale and Objectives,” https://projectatom.eu/index.php/project/background-rationale-and-objectives/

Text and photos by Ellen Engseth, Curator of Immigration History Research Center Archives and

Head of Migration and Social Services Collections,

University of Minnesota Libraries

Innovation around Migration

Regional Archives Sittard-Geleen / Archive De Domijnen is an archive located nearby two other countries. Between Belgium and Germany is the Regional Archives active in the Dutch municipalities Sittard-Geleen and Stein, although materials from other surrounding municipalities are also preserved. And this means also materials from our surrounding countries. This is self-evident, because people have been migrating for many centurie s! And for many centuries, our region has been an intersection of cultures. Our current municipality Sittard-Geleen existed 250 years ago of four ‘countries’. Sittard and various villages were Jülich (the German duchy of Jülich), Geleen was a Spanish and later an Austrian county, while there were also two mini-states: Limbricht and Obbicht, though these came later more and more under Jülich and Guelders reign. Long story short, a very complicated history in our region and the entire province of Limburg. Our archival sources are spread throughout Europe!

In the AToM-project, the four partner organisations hold several dozen interviews through oral history, or actually: video history. The focus can differ. In Spain, for example, the thirties are a central theme, the period wherein the civil war caused big migration flows. In our case, we interview people from many diverse migration flows, both emigrants and immigrants. From the collected materials, the partners make a virtual exhibition, of which the Spanish State Archives are the leading partner. In addition to that, each of the participants will also create their own presentation. We, as the Regional Archives, will organise our exhibition in 2025 in collaboration with students from the Radboud University in Nijmegen.

We do this in a way that differs slightly from the usual. Not we, but the students have the lead. They do this in a course called the ‘denktank’ (‘think thank’). A group of six students from the minor Migration and Cultural Contacts at the Radboud University in Nijmegen will help us with suggestions and examples on how these migration stories, the oral histories, may be presented in a physical exhibition. They received a briefing from us about the project and about the exhibition, and with the materials, they can make a plan for the presentation. How can the oral histories be presented in a physical exhibition? And where? Will this presentation be in the museum, a library, a community centre, or somewhere else? Or a combination of these locations? Combining stories with archival materials, art, and maybe even music, is a possibility. And even more, the year 2025, in our city, in a collaboration between the archive, Museum Het Nieuwe Domein and De Domijnen, and the society, will be themed ‘the year of loves’ . Here we also find connections to migration stories: are these often not also stories where love is a central theme? Migrating for love, but also to give your loved ones the best, the safest, life possible.

We are curious where this search of young and creative thinkers, combined with the oral histories, will lead us. You are welcome to see the result in Sittard-Geleen in 2025!

Written by: Peer Boselie

Translated by: Nina Vogels

IBERO-AMERICAN MIGRATORY MOVEMENTS PORTAL

The Spanish State Archives are legally mandated, as the coordinating body of the Spanish Archive system, to promote cooperation with other countries and cultural spheres, especially with the countries of the European Union, Latin America and the Mediterranean, in digitisation programmes and in the creation and development of Internet platforms and portals, with the aim of promoting knowledge and dissemination of the documents which form part of our common history.1

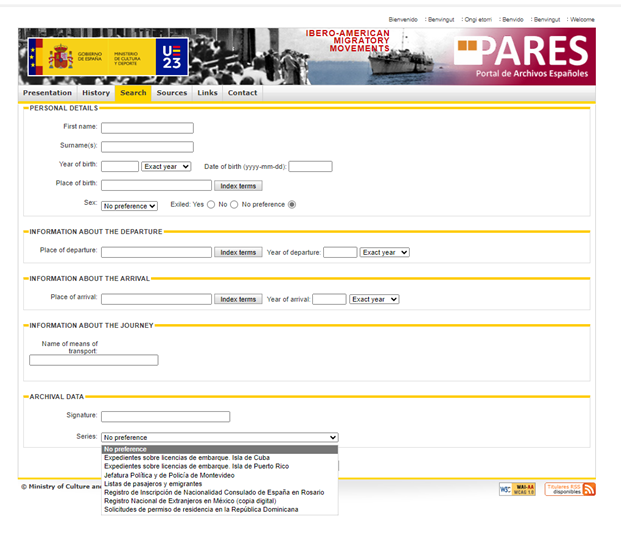

In the development of these competencies, the Ibero-American Migratory Movements Portal 2 was created in 2010 with the aim of rescuing and disseminating collections relating to the emigration and exile of Spaniards to Ibero-America in contemporary times. Developed as a microsite of the Portal of Spanish Archives (PARES), this Portal is a digital repository through which one can access information and documents that bear witness to the circumstances of the emigration of thousands of Spaniards to Ibero-American countries.

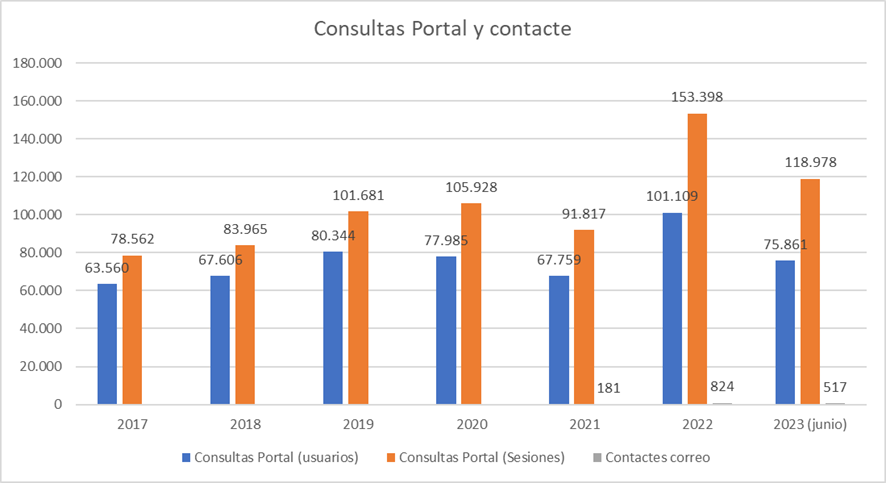

The Portal offers information on emigrants online and allows the downloading of documents with migratory content from the period in which mass emigration took place, which is circumscribed between the last third of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century. It also shows documentation of the Republican exile, so the Portal contains information on both economic emigrants and those who left Spanish territory for political reasons in the decade of the thirties and forties of the 20th century. The idea of creating a web portal with these characteristics had its origins in the need to facilitate access to the documentation of the period of greatest influx of Spanish emigrants, taking into account that, since the enactment of the Law of Democratic Memory3 , the interest of many Latin American citizens in the archives and documents that bear witness to the circumstances and dates of their ancestors’ journeys has grown considerably (see graphic 1).

Currently, the Portal offers 77,481 records4 of emigrants, allowing the search by different criteria, for example, through the known personal data of the emigrants, the places of departure or destination, the dates of the journey, the name of the ships that transported them or by the condition of exile, among others.

Through these filtering possibilities (see figures 2 and 3), the Ibero-American Migratory Movements Portal promotes the dissemination of archival documentation of migratory content, with the intention of supporting historical research, but fundamentally to facilitate citizens’ access to documents and ensure the right to information and knowledge of people, many of whom are direct descendants of emigrants.

The Portal is the result of cooperation between several Spanish and Latin American archives and its contents are progressively updated and increased as the work of archival description and digitisation of documentation progresses, as well as through the signing of collaboration agreements with countries interested in disseminating this type of documentation. At the moment, the Portal contains documents from the following archives: Archivo General de la Administración (Spain), Archivo General de Indias (Spain), Archivo General de la Nación de México, Archivo General de la Nación de República Dominicana, Archivo General de la Nación de Uruguay and the Fundación Complejo Complejo Cultural Parque de España (Argentina).

The description of the documentary series contained in the Portal has been carried out using the structure of elements of the ISAD (G) standard. However, an analytical description of the documentary units has been considered in order to extract as much information as possible about the emigrants and thus facilitate their search. This data has been entered in a standardised form, using the Standard for the development of standardised access points for institutions, persons, families, places and subjects in the archival description system of the State Archives.

In addition to the search engine for emigrants, which allows multiple filtering options to be combined, the Portal incorporates a guide to documentary sources for the study of Spanish emigration, structured by archives in Spain and America, which is the result of intensive research on the subject.

The Portal also includes an electronic contact form through which citizens’ queries on the search for emigrants can be answered.

The personal details of emigrants that feature on this portal are taken from the following document series :

Listas de pasajeros y emigrantes del Consulado de España en Veracruz [Lists of passengers and emigrants from the Spanish Consulate in Veracruz] (Spanish National Archive, Spain)

Expedientes de licencias de embarque a la Isla de Cuba y Puerto Rico [Files of boarding permits for travelling to Cuba and Puerto Rico] (General Archive of the Indies, Spain)

Registro Nacional de Extranjeros en México [National Register of Foreigners in Mexico] (Mexican National and State Archives)

Solicitudes de permisos de residencia en la República Dominicana [Requests for residency permits for the Dominican Republic] (General State Archive of the Dominican Republic)

Libros de Pasajeros de Policía de Montevideo [Passenger Log Books of the Montevideo Police] (General State Archive of Uruguay).

Registro de Nacionalidad del Consulado de España en Rosario [Nationality Register of the Spanish Consulate in Rosario] (Parque de España Complex Foundation in Argentina

Cristina Díaz Martínez, Head of Institutional Relations. Spanish State Archives

1 Art. 3 f) of Royal Decree 1708/2011, of 18 November, which establishes the Spanish Archive System and regulates the Archive System of the General State Administration and its Public Bodies and its access regime.

2 http://pares.mcu.es/MovimientosMigratorios

3 Law 20/2022 of 19 October on Democratic Memory.

4 The data provided in this article are as of 28 September 2023.

Guide to the 1939 Spanish Exile in the National Archives

The preservation of the documentary memory is a duty of the Spanish State, which is exercised through the Ministry of Culture and Sport, delegated to the General Sub-Directorate of the National Archives (SGAE), an organism that has been working to recover the documentation dispersed by the Exile of 1939.

With the turn of the millennium, an increase in social demand for the documentation of this historical period has also been noted, to such an extent that it has been Spanish society itself that has been demanding the dissemination on the Internet of documentary collections on the Civil War, Francoism, and Exile, whether these are kept in Spain or abroad.

For all these reasons, in 2019 and coinciding with the 80th anniversary of the beginning of the republican Exile, the SGAE published on its institutional website the Guide to the 1939 Spanish Exile in the National Archives, a microsite that compiled the informational resources of the Spanish National Archives on the subject[1].

The Spanish Republican Exile affected at least half a million people, who were forced to leave Spain after the Francoist victory in the Civil War. The main host countries of the diaspora were France, Argentina, and Mexico, the latter of which took in more than 200,000 Spanish refugees. Other destinations of Spanish exiles were Chile, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. Moreover, around 9,000 Spaniards are known to have been deported to Nazi concentration camps.

The aim of the Exile Guide is educational, and therefore it has been structured around sections, as the main threads of the story of the Spanish diaspora in 1939, after the end of the Civil War and the beginning of Franco’s regime:

1. Exiled archivists and librarians

The first thread highlights the crucial role that some members of the Faculty of Archivists, Librarians, and Archaeologists played in safeguarding Spain’s historical, artistic, documentary, and bibliographic heritage during the Civil War. Later, after the defeat and their journey into exile, these professionals continued their cultural work, contributing to the development of the profession in their host countries.

2. Refugee ships

The end of the war meant the diaspora of hundreds of thousands of Spaniards that had remained loyal to the government of the Second Republic. The fate of the defeated was to head into exile. The refugee ships on which these Spaniards embarked were the silent witness to the colossal exodus.

The main ships are identified which, through successive maritime voyages across the Atlantic, took the Spanish refugees and their families to the countries that offered to help them start a new life. In some cases, they did not find accommodation at their initial destination and had to re-emigrate to third countries by making new voyages by boat.

3. Aid Organisations

The third section lists the main humanitarian aid entities created by the government of the Second Spanish Republic with the aim of organising and channelling the massive departure of Spanish refugees to their new destinations once the war had ended. Thus, the leading maritime expeditions were the work of organisations such as the SERE and the JARE, with the collaboration of diplomats and politicians from various countries, especially Mexico.

4. Children of War

The fourth section covers the evacuation and repatriation of children. With the advance of the war front, it proved necessary to protect the civilian population by organising expeditions to evacuate more than 50,000 children to safety. In some cases, it was a temporary evacuation to get them away from the conflict, but in others, it entailed a non-return to their homeland due to the outcome of the war. They are known as the “Children of War”. The expedition of the Children of Morelia was the first of them all.

5. Refugee Camps

The fifth section provides an account of the refugee camps in the French Midi, which the French government set up near the border with Spain in the early months of 1939, close to the conclusion of the Civil War. These camps housed tens of thousands of defeated Spanish refugees, who had crossed the border into France to flee the reprisals of the Francoist faction.

6. Documentary resources

Finally, the last section of the Guide provides more in-depth information resources on the subject so as to enable the user to study the topics of interest in more depth.

To end, the SGAE continues to disseminate content on the 1939 Exile, and nowadays nearly six thousand records of Spanish exiles from the Civil War, linked to their archival documents, are available on the Spanish Archive Portal (PARES) for consultation on the Internet[2].

Josefa Villanueva, Archives Document Information Centre (CIDA)

Impressions about Migrations from an Archival Perspective

Why should we care?

Talking about the social responsibility of cultural heritage institutions in general seems to have attracted more attention of late, and with good reason. Cultural heritage professionals tend to overlook the social importance of their work too easily, and archives devote too much effort exclusively to the heritage aspect of their mission.

We should care about documenting the history of migration because being socially responsible is part of our professional ethics. We should care because what we choose to archive can make a difference, be it for someone who searches for their family history, someone who tries to claim their civil rights by using historical records, or for someone conducting a scholarly research. We should care because we can help the communities and individuals who are studying their past now, and we could help them in the future – if our professional practices recognize the need for such action.

Why are archives and migration strongly related topics?

This introductory blog entry about the Archives and Traces of Migration project broaches and expounds ICARUS Croatia’s internal motivation to engage in discussion about migration, a topic that is by nature dynamic and, one might feel, in contrast with the static nature of archives and archival policies. The idea was to investigate migration from the perspective of how it is reflected in historical records, as well as to investigate archival policies and practices regarding this globally important social phenomenon. Archives document migration, most of them not actively, but, nonetheless, their holdings allow for the history of migration to be reconstructed and written about it, based on the facts contained in documents. As to how archives treat such documentation, that is an open question, one certainly worth looking into.

We often perceive archives only as places of the past, as institutions that keep someone’s written heritage and important records. But, at the same time, archives are places that shape the future, for what is written and recorded now will make a difference later. Some people and some communities will be able to claim their rights through historical records, some will not. It will be possible to write some books, but not all. We should care because the decisions we make now will affect future possibilities.

Connecting the history of various communities with the cultural narrative of one’s homeland and host land through archival records is an amazing opportunity for any society. We should care because we preserve and hold these records as a means of connection.

Enabling the use of archival records for the purposes of a person exercising their rights is one of the central values of archival work, regardless of the type of archive. Archival records, as well as archives themselves, have the potential to help people. We should care because our practices can help hold people accountable for their actions and provide ample evidence.

What challenges are archivists faced with?

The first challenge we have detected is that many archives are often unfit to deal with any other agenda aside from the one preassigned to the institution. It is difficult to find additional resources that would allow the archives to engage in extra and additional work.

The big challenge is how to address the archival heritage of the Other (the Other being any group of migrants, both immigrants and emigrants). Dealing with the Other has been the preoccupation of heritage professionals and a wide range of scholars, from early ethnographic studies to contemporary anthropological research. Contemporary archival studies wish to include the Other as a co-creator, in a participatory and post-custodial manner. In archival practices, this would present as much a challenge as an opportunity.

Historical records and archival heritage transcend country borders, even though archival policies and practices abide by them. Understanding different archival traditions and working across them is a task that demands numerous skills. Real and metaphorical borders govern over so many factors. It is not just people who migrate, but their records as well, ending up outside the jurisdiction of national archives. And yet, the decisions on how to manage their records, the heritage that the migrants brought with them, are made within the context of one archival system.

In many European countries, archives have for decades now been involved in gathering both records and information about records from the emigrant population of their respective countries. The archives also collect and preserve records about historical national minorities and immigrants. The challenge might be in approaching them in the same manner of ethics of care.

Researchers are accustomed to using archival records in a way that was never intended by their creator, or even the archivists. An average citizen with no research skills, on the other hand, might need more help in using the archives. How do we design systems and services that they will find useful?

There are numerous challenges to be dealt with, as well as opportunities to look forward to. The cultural heritage of migrants is complex. It warrants a cautious, transnational approach, upskilling in numerous domains and, most important of all, understanding. We hope to get closer to achieving this goal within the AToM project.

Credit: text and photographs by Tamara Štefanac