Guide to the 1939 Spanish Exile in the National Archives

The preservation of the documentary memory is a duty of the Spanish State, which is exercised through the Ministry of Culture and Sport, delegated to the General Sub-Directorate of the National Archives (SGAE), an organism that has been working to recover the documentation dispersed by the Exile of 1939.

With the turn of the millennium, an increase in social demand for the documentation of this historical period has also been noted, to such an extent that it has been Spanish society itself that has been demanding the dissemination on the Internet of documentary collections on the Civil War, Francoism, and Exile, whether these are kept in Spain or abroad.

For all these reasons, in 2019 and coinciding with the 80th anniversary of the beginning of the republican Exile, the SGAE published on its institutional website the Guide to the 1939 Spanish Exile in the National Archives, a microsite that compiled the informational resources of the Spanish National Archives on the subject[1].

The Spanish Republican Exile affected at least half a million people, who were forced to leave Spain after the Francoist victory in the Civil War. The main host countries of the diaspora were France, Argentina, and Mexico, the latter of which took in more than 200,000 Spanish refugees. Other destinations of Spanish exiles were Chile, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. Moreover, around 9,000 Spaniards are known to have been deported to Nazi concentration camps.

The aim of the Exile Guide is educational, and therefore it has been structured around sections, as the main threads of the story of the Spanish diaspora in 1939, after the end of the Civil War and the beginning of Franco’s regime:

1. Exiled archivists and librarians

The first thread highlights the crucial role that some members of the Faculty of Archivists, Librarians, and Archaeologists played in safeguarding Spain’s historical, artistic, documentary, and bibliographic heritage during the Civil War. Later, after the defeat and their journey into exile, these professionals continued their cultural work, contributing to the development of the profession in their host countries.

2. Refugee ships

The end of the war meant the diaspora of hundreds of thousands of Spaniards that had remained loyal to the government of the Second Republic. The fate of the defeated was to head into exile. The refugee ships on which these Spaniards embarked were the silent witness to the colossal exodus.

The main ships are identified which, through successive maritime voyages across the Atlantic, took the Spanish refugees and their families to the countries that offered to help them start a new life. In some cases, they did not find accommodation at their initial destination and had to re-emigrate to third countries by making new voyages by boat.

3. Aid Organisations

The third section lists the main humanitarian aid entities created by the government of the Second Spanish Republic with the aim of organising and channelling the massive departure of Spanish refugees to their new destinations once the war had ended. Thus, the leading maritime expeditions were the work of organisations such as the SERE and the JARE, with the collaboration of diplomats and politicians from various countries, especially Mexico.

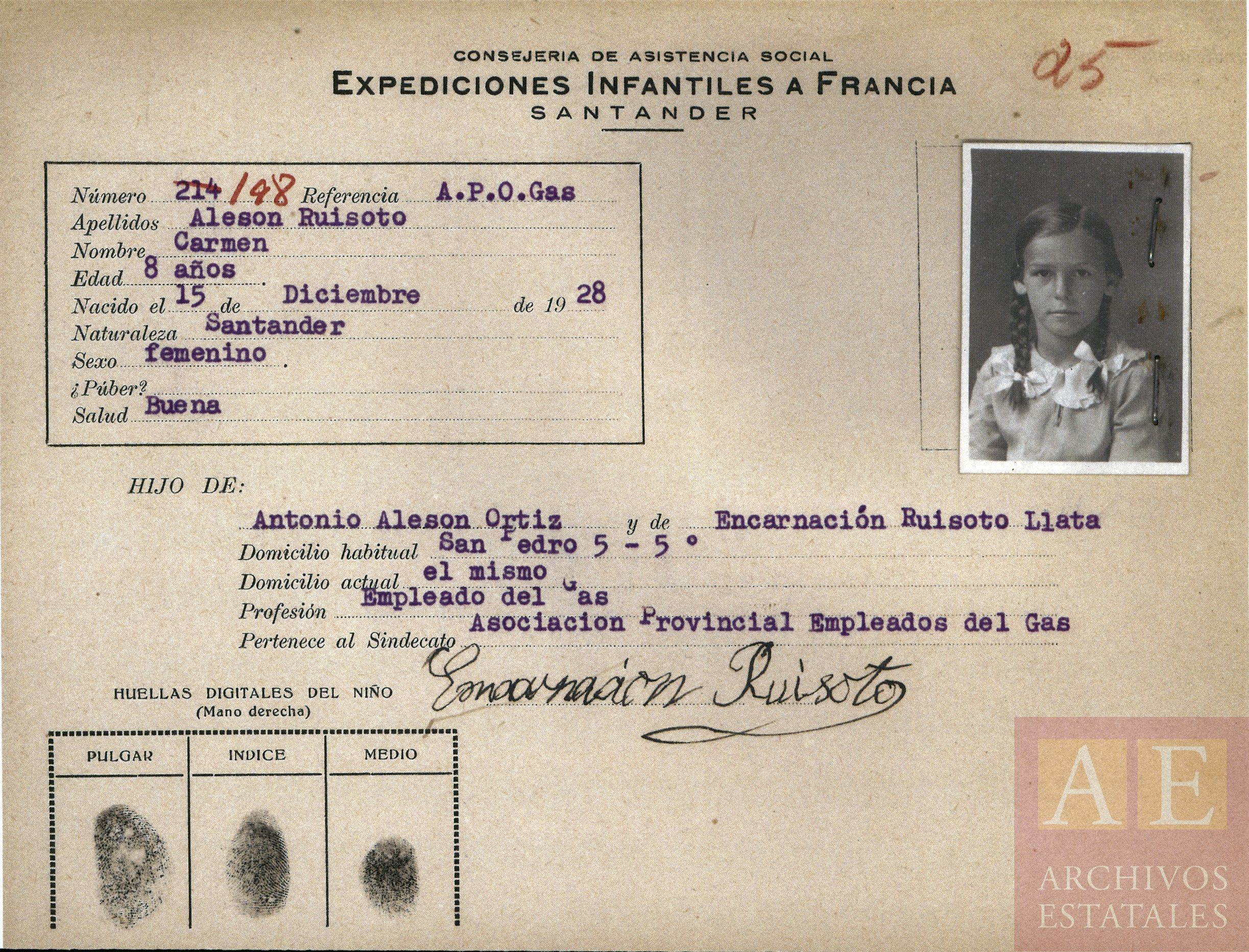

4. Children of War

The fourth section covers the evacuation and repatriation of children. With the advance of the war front, it proved necessary to protect the civilian population by organising expeditions to evacuate more than 50,000 children to safety. In some cases, it was a temporary evacuation to get them away from the conflict, but in others, it entailed a non-return to their homeland due to the outcome of the war. They are known as the “Children of War”. The expedition of the Children of Morelia was the first of them all.

5. Refugee Camps

The fifth section provides an account of the refugee camps in the French Midi, which the French government set up near the border with Spain in the early months of 1939, close to the conclusion of the Civil War. These camps housed tens of thousands of defeated Spanish refugees, who had crossed the border into France to flee the reprisals of the Francoist faction.

6. Documentary resources

Finally, the last section of the Guide provides more in-depth information resources on the subject so as to enable the user to study the topics of interest in more depth.

To end, the SGAE continues to disseminate content on the 1939 Exile, and nowadays nearly six thousand records of Spanish exiles from the Civil War, linked to their archival documents, are available on the Spanish Archive Portal (PARES) for consultation on the Internet[2].

Josefa Villanueva, Archives Document Information Centre (CIDA)

[1]Exile Guide: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura/areas/archivos/mc/centros/cida/4-difusion-cooperacion/4-2-guias-de-lectura/guia-exilio-espanol-1939-archivos-estatales.html

[2] PARES: http://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/autoridad/103530

Impressions about Migrations from an Archival Perspective

Why should we care?

Talking about the social responsibility of cultural heritage institutions in general seems to have attracted more attention of late, and with good reason. Cultural heritage professionals tend to overlook the social importance of their work too easily, and archives devote too much effort exclusively to the heritage aspect of their mission.

We should care about documenting the history of migration because being socially responsible is part of our professional ethics. We should care because what we choose to archive can make a difference, be it for someone who searches for their family history, someone who tries to claim their civil rights by using historical records, or for someone conducting a scholarly research. We should care because we can help the communities and individuals who are studying their past now, and we could help them in the future – if our professional practices recognize the need for such action.

Why are archives and migration strongly related topics?

This introductory blog entry about the Archives and Traces of Migration project broaches and expounds ICARUS Croatia’s internal motivation to engage in discussion about migration, a topic that is by nature dynamic and, one might feel, in contrast with the static nature of archives and archival policies. The idea was to investigate migration from the perspective of how it is reflected in historical records, as well as to investigate archival policies and practices regarding this globally important social phenomenon. Archives document migration, most of them not actively, but, nonetheless, their holdings allow for the history of migration to be reconstructed and written about it, based on the facts contained in documents. As to how archives treat such documentation, that is an open question, one certainly worth looking into.

We often perceive archives only as places of the past, as institutions that keep someone’s written heritage and important records. But, at the same time, archives are places that shape the future, for what is written and recorded now will make a difference later. Some people and some communities will be able to claim their rights through historical records, some will not. It will be possible to write some books, but not all. We should care because the decisions we make now will affect future possibilities.

Connecting the history of various communities with the cultural narrative of one’s homeland and host land through archival records is an amazing opportunity for any society. We should care because we preserve and hold these records as a means of connection.

Enabling the use of archival records for the purposes of a person exercising their rights is one of the central values of archival work, regardless of the type of archive. Archival records, as well as archives themselves, have the potential to help people. We should care because our practices can help hold people accountable for their actions and provide ample evidence.

What challenges are archivists faced with?

The first challenge we have detected is that many archives are often unfit to deal with any other agenda aside from the one preassigned to the institution. It is difficult to find additional resources that would allow the archives to engage in extra and additional work.

The big challenge is how to address the archival heritage of the Other (the Other being any group of migrants, both immigrants and emigrants). Dealing with the Other has been the preoccupation of heritage professionals and a wide range of scholars, from early ethnographic studies to contemporary anthropological research. Contemporary archival studies wish to include the Other as a co-creator, in a participatory and post-custodial manner. In archival practices, this would present as much a challenge as an opportunity.

Historical records and archival heritage transcend country borders, even though archival policies and practices abide by them. Understanding different archival traditions and working across them is a task that demands numerous skills. Real and metaphorical borders govern over so many factors. It is not just people who migrate, but their records as well, ending up outside the jurisdiction of national archives. And yet, the decisions on how to manage their records, the heritage that the migrants brought with them, are made within the context of one archival system.

In many European countries, archives have for decades now been involved in gathering both records and information about records from the emigrant population of their respective countries. The archives also collect and preserve records about historical national minorities and immigrants. The challenge might be in approaching them in the same manner of ethics of care.

Researchers are accustomed to using archival records in a way that was never intended by their creator, or even the archivists. An average citizen with no research skills, on the other hand, might need more help in using the archives. How do we design systems and services that they will find useful?

There are numerous challenges to be dealt with, as well as opportunities to look forward to. The cultural heritage of migrants is complex. It warrants a cautious, transnational approach, upskilling in numerous domains and, most important of all, understanding. We hope to get closer to achieving this goal within the AToM project.

Credit: text and photographs by Tamara Štefanac